Cooking: art, science, my greatest passion

I remember the first time I started cooking. I must have been 11 or 12. I was left to my own devices as my parents were both industrious business owners, so I tried my hand at making a seemingly simple egg omelette. To say the least, it ended up looking up like an oily abomination with some parts overcooked, and some parts still raw; it was cheese oozing out of a scrambled mess.

Since then, cooking has become my greatest passion. I didn’t realize it until recently, but cooking is unique in its ability to be an art form, science, and social event; it allows me to explore my creative side while still being practical.

For me, cooking is an art form. When I go to a restaurant and taste something truly unique, I am appreciating something the chef has spent years perfecting. Every bite is an exploration into the experience and deliberation of an artist, which in turn makes me wonder about what I am doing. Revelations of flavor profiling and complementary textures deepen my understanding of my own cooking, inspiring me to go further and try new things. It’s this constant challenge to push the boundaries of the aesthetics, smells, and tastes of my dishes through inspiration of my own—or more likely drawn from others—which pushes my cooking.

I suspect that another reason why I love to cook is because of my love of science. You can only really become a great chef through the scientific method. Researching why certain ingredients impart certain flavors or create certain reactions, and then recreating those experiments by testing them in the kitchen, is what got me to read hundreds of pages’ worth of cookbooks and then try the recipes on friends and family. A great example of this is one of my favorite recipes, Spaghetti Aglio e Olio. The only ingredients are pasta, olive oil, and garlic. If you were to just haphazardly throw these three ingredients into a pan without any prior knowledge, you’d end up with an oily, garlicky mess. But once you learn to retain the water from cooking the pasta—because it contains leftover starch, which emulsifies the fatty olive oil, creating a heavenly, creamy sauce which then sticks to the pasta—you can create a delicious dish worthy of any date night.

Cooking also allows me to do things for others: it has this magical ability to bring together friends and family more than any other social event. Few things satisfy me as much as the sound of silence when a table of friends dig into something which I’ve spent hours crafting.

But don’t get me wrong. More than anything, I love when I receive criticism. Sometimes people are afraid to criticize my cooking because they know that I spent many hours—and oftentimes many dollars—to create this dish for them. It’s a labor of love, and mentioning that the steak was too salty seems rude. However, it’s only through criticism that I am able to refine my technique. In her book, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, Angela Duckworth writes, “Experts hungrily seek feedback on how they did. Necessarily, much of that feedback is negative. This means that experts are more interested in what they did wrong—so they can fix it—than what they did right. The active processing of this feedback is as essential as its immediacy.” I get more excited when a friend gives my food a critique or suggestion than when they shower me with compliments, and when I’ve reached the point where I no longer get criticism, I’ll quickly lose interest and move on to make mistakes elsewhere to further my abilities.

Much like any other skill, cooking takes hundreds of accrued experiences and failed attempts to develop even a basic mastery of the skills required to make a palatable dish. From learning to toss food in a skillet, to learning how to use a knife, to understanding how much salt I need to add, I can point to a myriad of spills, grease fires, cuts, over-salted dishes, and disgusting combinations I had to go through to learn what I know now. It’s this constant evolution and eventual mastery that makes me cook time and time again.

Going back to Duckworth’s book, she writes, “Passion for your work is a little bit of discovery, followed by a lot of development, and then a lifetime of deepening.” Now that I know I can make good food after years of developing my skill, I’ve reached a point where I always try to push the boundaries; tweak that recipe a little bit here, test a new method of cooking there. Whenever I make something, I’m always changing how I do things, always running after the ideal, knowing I’ll never reach it.

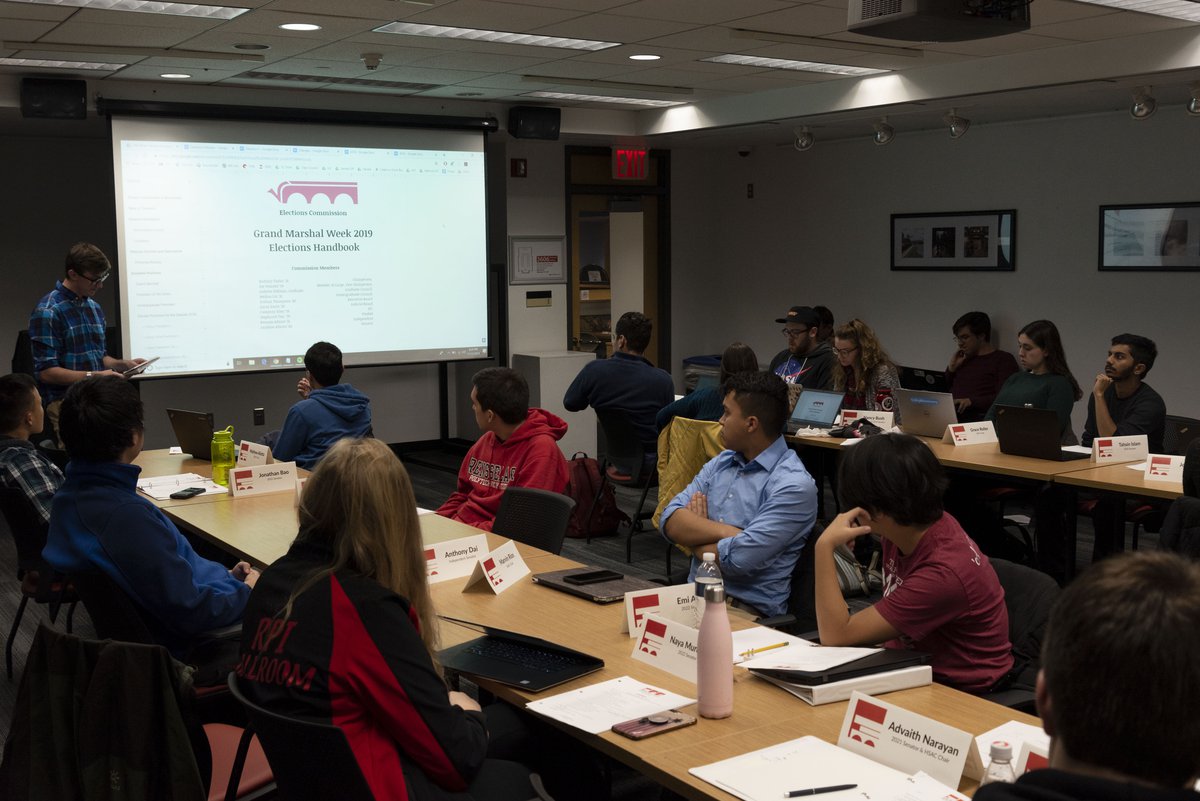

Student Senate

Student Senate

Restaurant Review

Restaurant Review

Tv Series Review

Tv Series Review