Dehumanization in work, war explained

Associate Professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University Jennifer Rhee discussed concepts from her book, The Robotic Imaginary: The Human and the Price of Dehumanized Labor, during the first Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center talk of the Spring semester.

After thanking EMPAC and Rensselaer staff, Rhee posed questions about humanity and labor: who is considered human? Whose labor cannot be automated and, ultimately, whose suffering is prioritized? Attendees were challenged to think about the cost of freedom for some at the expense of others, and how to extrapolate this to the labor force and beyond.

Though women are crucial to the workforce and are the backbone of the global economy, Rhee says technologies such as Alexa and Siri reflect the devaluation of what she calls “care labor,” historically thought to be provided by women and not valued as work. This mentality carried over into the representation of women in certain fields, according to Rhee, resulting in a trend of decreased wages and overrepresentation in secretarial jobs.

A majority of Rhee’s talk focused on drone warfare as another mode of racial dehumanization and how drone policy systematically discriminates and propagates racial violence in the United States and overseas at the expense of civilians. Rhee cited Norbert Wiener’s The Human Use of Human Beings in discussing how drones seek to predict the “enemy other’s” behavior patterns. In tandem to what I’m learning in my Science, Technology, and Society classes—emphasis over the “other” and how this influences the way we take on or deflect responsibility and action—I thought it was interesting how Wiener questioned how the United States allowed German soldiers to maintain their humanity but the Japanese soldiers were dehumanized. Dehumanizing language carried over to the jargon of war; calling humans on the ground “ants” and those killed as “bugsplats” continues to shape the way we view already dehumanized targets.

As for the technological intimacy of military and police departments, Rhee referenced the satiric artwork of street artist Essam Attia that serves as a testament of the normalization of drone strikes within communities of color. She referenced piercing posters of New York Police Department drones firing a missile at a fleeing family and a parody of a street cleaning or towing sign, which stated “authorized drone strike zone 8 am—8 pm including Sunday.”

Rhee stressed the importance of the limitations of technologies when she said, “drone omniscience is a fallacy,” granting a false sense of security that a human can know everything. According to Rhee, Dronestagram, started by James Bridle, highlights the limitations of drone vision and the disparity between the before and after of a drone strike. The sterile image never shows the horror and chaos caused by drone strikes in its aftermath. With the projection of a silhouette of a young male on a bike on a dirt road, Rhee brought up the point of how drone strikers make the determination of whether a person is a young adolescent civilian boy or a man of military age is a uniquely human decision, and how we don’t normally think of the human drone operator behind the drone strikes.

Student Rights

Student Rights

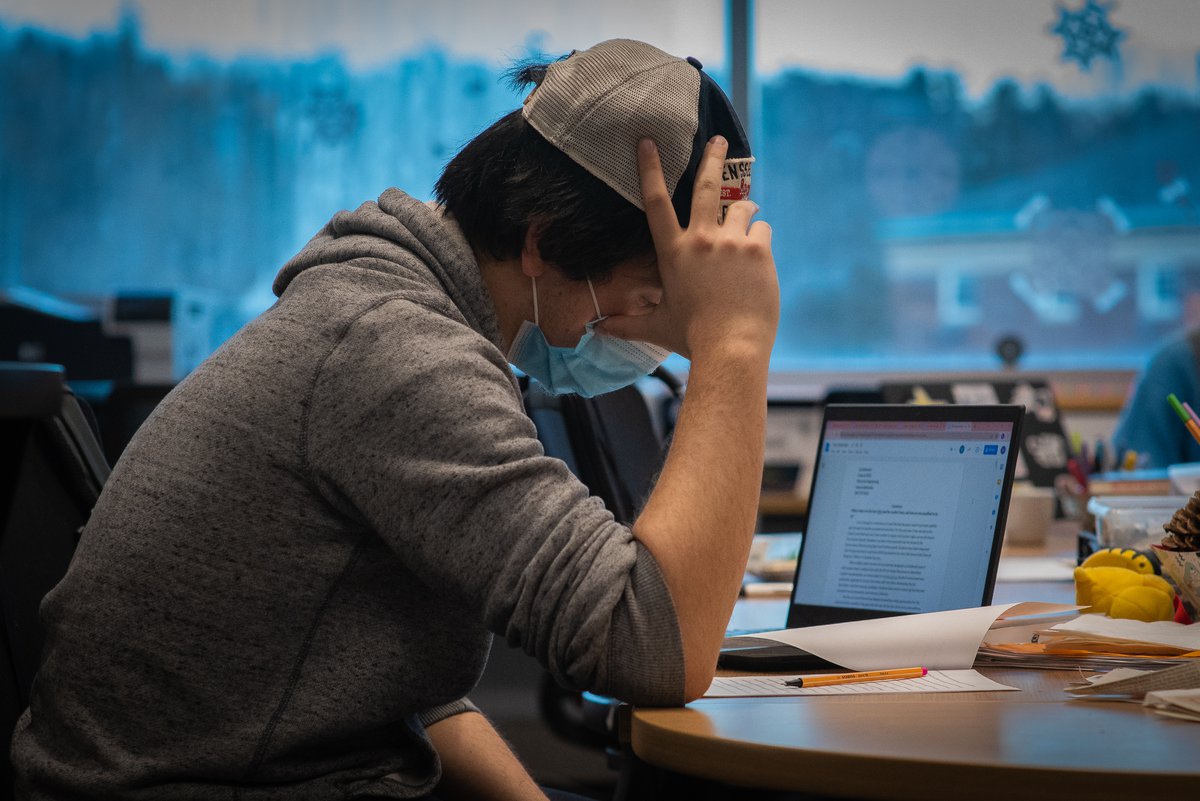

Academics

Academics

Editorial Notebook

Editorial Notebook

Campus Security

Campus Security