Breaking the shackles of the prisoner’s dilemma

Many people will argue that it is easy to be kind. Simple tasks like holding the door open for others, being polite, and treating strangers with respect aren’t hard and can become a habit over time. What many people won’t argue for—and some might even argue against—is that it is easy to be selfless.

We live in a world of give and take. We mostly execute actions that result in a favorable outcome for ourselves. Being a student at RPI is an example of this process: we pay tuition and attend school for 3-5 years, then expect RPI to give us a degree in return.

Some actions exist outside this give and take nature. There are actions that are harmful to every party involved, like being rude or hurting a loved one. These actions don’t make sense to perform as there is no benefit to anyone. The more interesting type of action is one that is helpful to others but not necessarily oneself. Being kind serves as a trivial example—there is no return for holding a door open besides the occasional “thank you”—but there are non-trivial actions that we must make in our lives. On RPI’s campus, this might be helping out other students or joining a service organization.

To analyze these actions another way, we can consider the prisoner’s dilemma, a simple thought experiment involving two prisoners in jail. In this experiment, the police offer each prisoner a deal: rat out the other prisoner to get out of jail. Accepting the deal will give the other prisoner a very long sentence, but gratifies the snitch. However, should both prisoners choose to testify, both will get a longer sentence than their current time, albeit not as long as if only one testified. Both prisoners are given this choice and know that the other prisoner also has this choice, but neither are allowed to talk to each other.

Immediately, the dilemma is apparent. Thinking of oneself alone is only beneficial if the other party does not also act selfishly. Both prisoners staying silent would result in the overall smallest sentence, but this requires trust and camaraderie.

Despite how simple the dilemma is, the experiment beautifully captures the real world conundrum of only acting in self-interest. We could get by with everyone acting only for themselves, such is the premise of capitalism, but these acts of selflessness can create joys otherwise missed. We can see this happen in clubs on campus. These clubs often have events that could not function unless all members helped out. Moreover, clubs can have welcome events open to non-members. While non-members are meant to enjoy these events—normally at no cost—if every attendee was a non-member, these events could not exist.

I believe the only correct answer to the prisoner’s dilemma is to trust one another. Even if it is riskier and can result in the worst outcome for oneself, it can also lead to the best outcome for every party involved. This translates to real life too. When we dedicate our time to helping others, like by joining clubs and hosting events, we can do more than we could possibly do by ourselves.

The risks of being too trusting are real and harmful. Being too selfless can lead to taking on too many responsibilities and being unfairly burdened. That being said, always living life as a traitorous prisoner is bound to backfire eventually.

Try joining a club! Or saying yes to more opportunities when they come by. Even if there doesn’t seem to be immediate merit, fruits of hope may be planted. If the world is full of bad people, become the first good one. Change the world by being the change you want to see in the world.

GM Week 2022

GM Week 2022

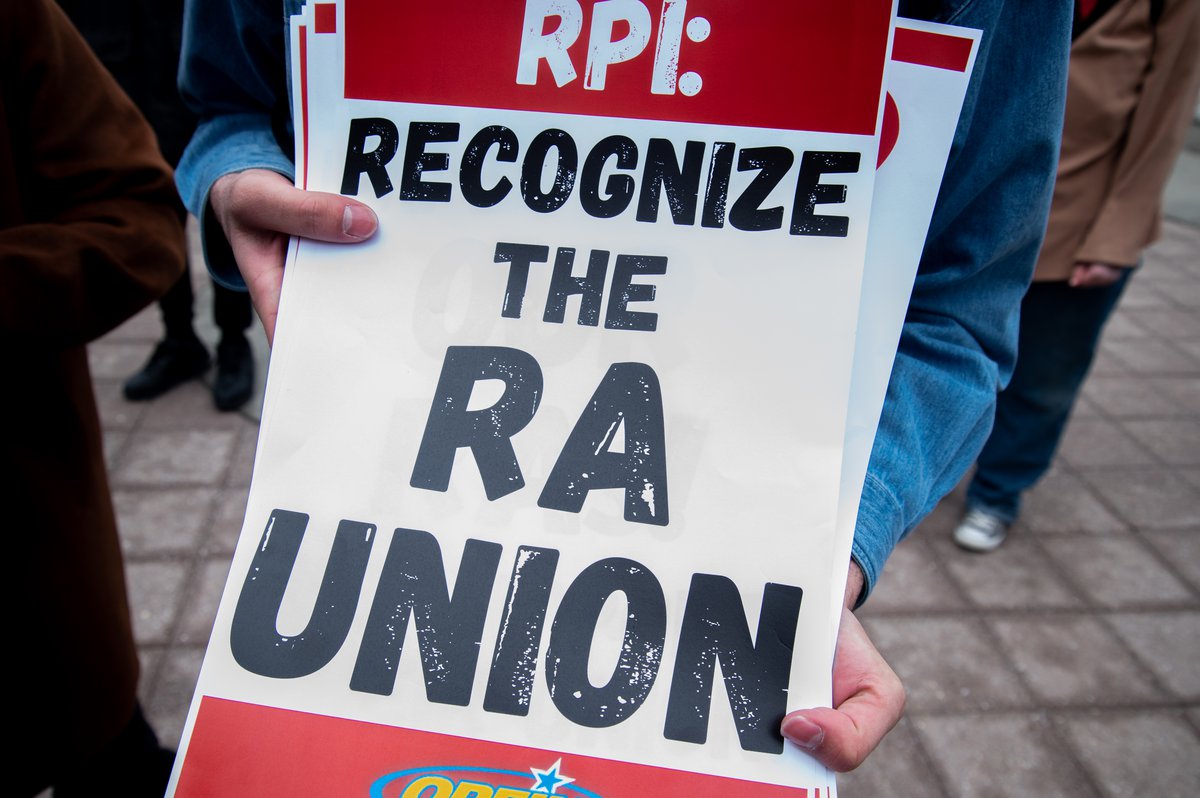

Student Activism

Student Activism