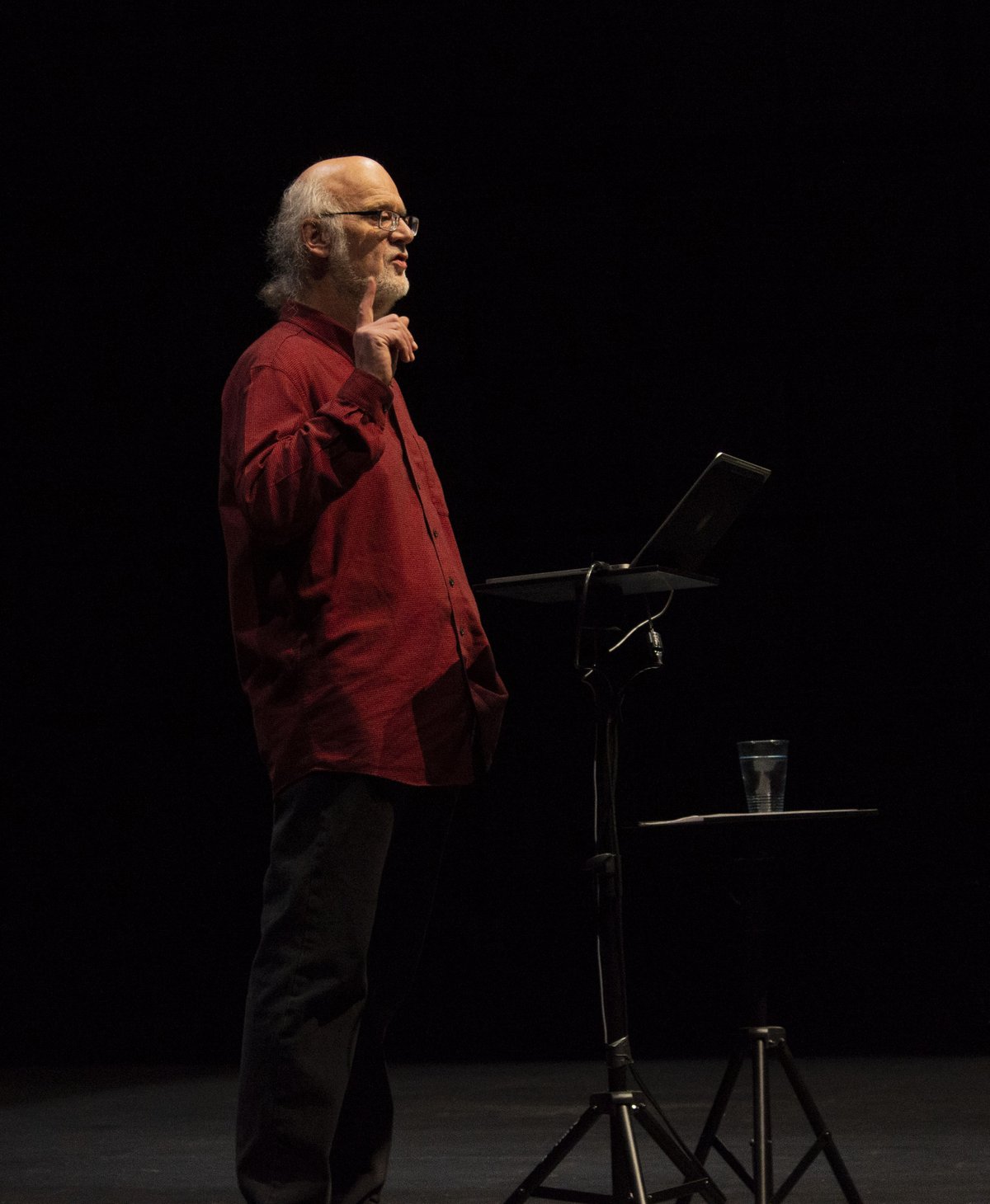

EMPAC director shares life’s work

Before Johannes Goebel assumed his role as director of the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center in 2002, he was involved in creative projects of all kinds ranging from handmade instruments to collage and spoken word pieces, as well as music and collaborations with artists of every type.

These past pursuits were the subject of “An EMPAC Salon,” a part-presentation, part-performance. Goebel’s hope was to communicate the personal influences he brought to EMPAC and how they shaped the space itself and the programming it currently offers.

Goebel opened the talk with photos and stories of his musical improvisation. In the 1970s, he and a group of friends filled a church’s choir with scrap metal instruments and what he called “denaturalized” instruments, like pianos with no keys or an old radio. The music they made was entirely “off-the-cuff;” a group of no more than four people would play until the piece was over, never looking at each other, only taking cues for what they should play from what they could hear the others playing.

Goebel was clear these works weren’t meant for others, just experimentation. “We played for ourselves,” he explained. Not only that, but Goebel encouraged others to play the same way. Driving his instruments around Germany, he created and implemented many different musical workshops, like one-on-one “lessons” with children, programs in hospitals, and over 400 workshops in schools.

This musical experience evolved when Goebel met composer John Chowning at the Darmstӓdter Ferienkurse, a prestigious set of summer music courses taught in Germany. He was introduced to computer-synthesized music and wanted to emulate the 3D sound that Chowning was creating. In 1977, he studied at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, as well as the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Goebel saw the development of all kinds of cutting-edge technologies, including the first digital audio workstation, and was especially influenced by Leland Smith’s SCORE music typography system.

Surrounded by computers, Goebel’s other art reflected on the relationship between man and machine, illustrated by his display of dada-influenced collage and typography and tongue-in-cheek spoken word, or, as listed in the EMPAC program, “non-scientific reflections on computers, artificial intelligence, and human-computer interaction.”

Goebel also showed his work after Stanford, including two large-scale projects, “Tabooh” in 1982 and “Kalisation” in 1985.

“Kalisation” was an installation in an abandoned potash mine outside. Goebel set this up after he realized the lifeless nature of the mountain of potassium tailings created a “moonscape” lacking any frame of reference for scale. The piece invited visitors to walk through the alien landscape in the early morning, starting at 4:30 am and ending three hours later. Visitors would walk through a narrow doorway in a cinderblock wall that was still under construction, before being led down a path where they could witness a faux archeological dig of a gigantic skeleton, an artist repeatedly staining the tailings red before cleaning them again and again, and body-painted performers wandering the hills. Noises from Goebel’s custom built instruments could be seen but not heard, mimicking the cries of birds, while another artist built card houses from panes of glass, rebuilding in vain as one after another were blown down and shattered.

“Tabooh” was an exhibit built in the Zuiderkerk in Amsterdam, where Goebel worked with an architect to create a unique space for sound and performance art within a historic church. Visitors were again funneled through a narrow entrance and greeted with textile art, music, unique architecture, and dance performances.

Goebel closed the talk with one more musical composition, “Of Crossing the River,” an 18-minute experience through four loudspeakers in each corner of the room. He explained that each person’s experience of the song’s length was different; some said it passed in five minutes, while it might have seemed like 50 for another. The piece centered around Goebel’s conclusion that computer-synthesized music should be fundamentally different from traditional music. Computers have no need to breathe or take pause, so the concept of notes doesn’t need to apply to the music they produce.

Droning at times and sharp at others, the concept of time was twisted, but not completely lost due to the nature of the space and audience. The sounds were unnatural but not inorganic, like a wormhole in a science fiction movie or a whale’s call through Jell-O. The unflinching persistency of the computer-synthesized tones built layers upon layers of noise, which rotated through the four loudspeakers, leaving a powerful silent void when they were stopped and restarted throughout the piece. When the piece was over, it almost felt like waking up—if it weren’t 10:30 at night.

A winding look back at EMPAC and the man that helped define it, “An EMPAC Salon” was a display of a multi-talented creative and his relationship with artistic pursuits of all kinds. Notably casual, the forum encouraged an audience-speaker relationship unlike a traditional talk, and I left with a far greater understanding of the campus’ newest building.

Greek Life

Greek Life

Opinion

Opinion

Opinion

Opinion