In the beginning

“Sometime during your life—in fact, very soon—you may find yourself reading a book, and you may notice that a book's first sentence can often tell you what sort of story your book contains.” Lemony Snicket opens The Miserable Mill with a line that may not summarize the rest of his novel, but does an excellent job of setting the scene for this particular article.

When writing a story, the prose must immediately draw people in. Readers won’t simply wait until the story gets good. They need to be engaged from the get-go. Oftentimes, the initial sentence illustrates the greater themes of the work, handing readers the thesis at the start as well as an interesting premise to reel them in.

Let’s take a look at some of the best introductory lines ever written. In creating my list, I focused on a specific criteria: each opener must stand on its own, not solely requiring the context or reputation of the book that it was cited from to uphold it.

- 1984 by George Orwell: “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

This quote perfectly encapsulates the thesis of the novel: totalitarianism has psychological effects that can dangerously manipulate memory. We know that analog clocks only go up to twelve. And yet, if something so fundamental to our everyday lives—like time—is altered, our very sense of being will be thrown off. With the distinct imagery provided, we get the sense that something is fundamentally not right in the world.

- Voyage of the Dawn Treader by C. S. Lewis: “There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.”

Lewis uses the first line of his book to introduce information about a character. At this point in the story—the absolute beginning—we know nothing about Eustance Clarence Scrubb except that he likely has a personality as tragic as his name.

- The Princess Bride by William Goldman: “This is my favorite book in all the world, though I have never read it.”

As dictated by cultural osmosis, it is likely that you’ve at least heard of this book—even if you’ve never seen the movie. To hear the author of the abridged version admit that he has never read the story he is about to tell is fascinating. It makes me want to settle down, grab a cup of tea, and listen to what will undoubtedly be a great yarn.

- City of Glass by Paul Auster: “It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.”

A mystery is always engrossing, but Auster uses phrasing—such as “in the dead of night”—to add a layer of unease to the events. Furthermore, the wrong number provokes a great number of questions: who is the person calling? Did something happen to the person that they are looking for? And why are they calling at such an odd hour?

- The Secret History by Donna Tartt: “The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.”

Most authors wait to kill off a main character until a titular moment in the plot, when they can shock the reader with a plot twist. It’s extremely compelling for Tartt to open her book with this bombshell. The tone of the sentence illustrates the eerie, macabre theme of the entire tale.

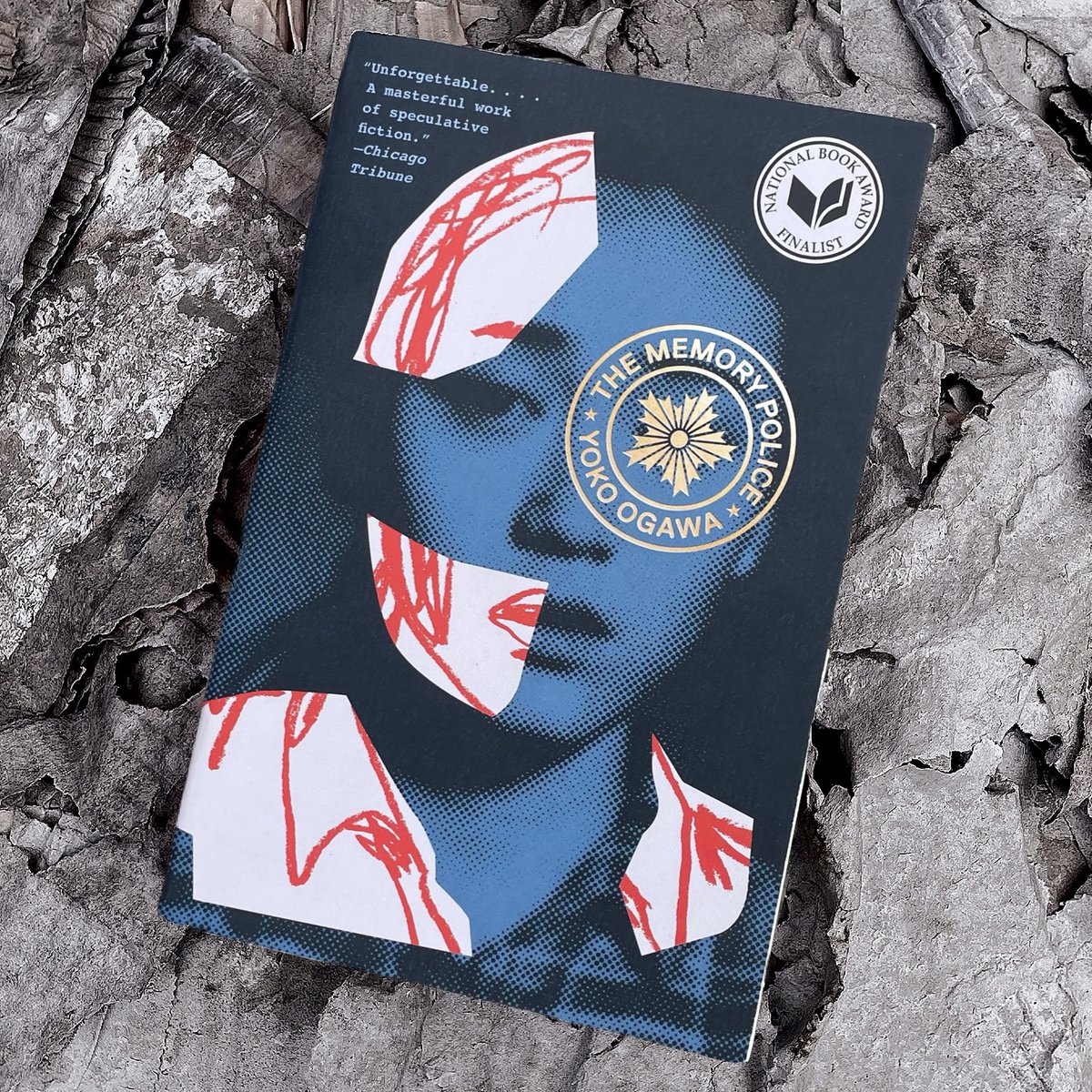

- Heading out to Wonderful by Robert Goolrick: “The thing is, all memory is fiction.”

With such a few words, Goolrick uses a simple statement to floor the audience with introspective contemplation. He proposes that the mind deceives through hindsight. If that’s true, can we trust our own memories?

- A Darker Shade of Magic by V. E. Schwab: “Kell wore a very peculiar coat. It had neither one side, which would be conventional, nor two, which would be unexpected, but several, which was, of course, impossible.”

Schwab’s lines are some of my favorites, as they intrigue the reader with an atmosphere of mystery, while laying the foundations of magic that carry strong throughout this novel and the rest of its series. As is common when the human brain encounters something incomprehensible, you immediately want to know more about this fantastical object, person, and world.

The start of a story can make or break the entire book. It sets the tone for the rest of the novel, giving readers some insight into the themes to come. A book’s first words can transcend history. They can be known across age, language, and religion as something that was said in the beginning.

Editorial Notebook

Editorial Notebook

Editorial Notebook

Editorial Notebook

Book Review

Book Review

Sports

Sports